Armenian Jerusalem

“whenever two Armenians meet . . .”

Krikor

Naregatsi

(Gegory

of

Nareg),

who

spent

his

entire

life

in

the

monastery,

died

at

the

relatively

young

age

of

50,

but

what

he

has

left

behind

has

outlived

his

time

and

age:

as

long

as

one

Armenian

heart

beats

anywhere

in

this

world,

his

inspired

odes

and

lamentations

will

continue

to

find

an

echo there.

His

writings,

described

by

critics

as

"literary

masterpieces

in

both

lyrical

verse

and

narrative,"

have

only

been

known

in

their

original

golden

Grapar

(Classical

Armenian)

to

a

select

cadre

of

Armenian

scholars,

an

oversight

now

boldly

atoned

for

by

the

eminent

expert

on

Medieval

Armenian literature, Dr Abraham Terian.

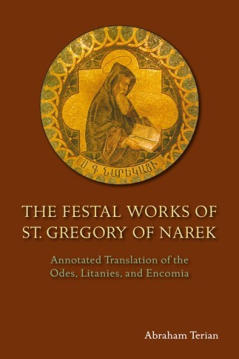

His

"groundbreaking"

and

"magnificent"

new

book,

"The

Festal

Works

of

St

Gregory

of

Narek"

(461

pp,

the

Liturgical

Press,

Minnesota,

2016)

is

the

first

translation

(embellished

with

54

pages

of

introduction

and

an

array

of

explanatory

notes)

in

any

language,

of

the

surviving

corpus

of

Naregatsi's

festal

works.

Terian's

mellifluous

English

and

his

mastery

of

Grapar,

have

made

this

onerous

task

a

joy

and

a

celebration.

Like

all

other

Jerusalem

Armenians,

Terian's

first

encounter

with

Naregatsi

occurred

at

a

tender

age,

when

at

the

graduation

ceremony

of

primary

students

at

the

Armenian

parish

school

he,

like

all

his

classmates,

was

handed

a

copy

of

a

Naregatsi

prayer

book,

the

"Aghotamadyan"

as

a

parting

gift,

to

be

his

guide

and

inspiration

for the days ahead.

The

tradition

continues

to

this

day.

I've

kept

my

own

copy

for

half

a

century,

and

remember

a

line

from

one

of

Naregatsi's

most

poignant

odes,

his

magnificat

of

God:

"The

darkness

of

the

night

cannot

eclipse

the

glory

and

grandeur

of

your

dominion"

(my

translation).

With

his

new

book

Terian,

who

has

won

plaudits

from

various

parts

of

the

world,

the

latest

his

acceptance

as

a

fellow

academician

(as

an

"orientalist")

by

the

Ambrosian

Academy

of Milan, escorts us into a new dimension of spirituality.

His

skill

in

penetrating

what

Harvard

professor

James

Russsell

calls

the

"extremely

sophisticated content and difficult language" of Nareg is particularly remarkable.

"His

work

is

more

than

a

monument

of

meticulous

scholarship,"

Russell

says.

"The

work

is

of such a high standard that it is unlikely to be equaled, much less superseded."

Naregatsi,

a

10th

Century

Armenian

poet,

mystical

philosopher,

theologian

and

saint

of

the

Armenian

church,

was

born

into

a

family

of

writers.

He

is

considered

"Armenia's

first

great

poet".

In

token

of

his

unique

achievements,

Pope

Francis

declared

him

a

Doctor

of

the

Universal Church in February last year.

"Saint

Gregory

knew

how

to

express

the

sentiments

of

your

people

more

than

anyone,"

he

said in a statement addressed to the Armenian church.

"He

gave

voice

to

the

cry,

which

became

a

prayer

of

a

sinful

and

sorrowful

humanity,

oppressed

by

the

anguish

of

its

powerlessness,

but

illuminated

by

the

splendor

of

God's

love

and

open

to

the

hope

of

his

salvific

intervention,

which

is

capable

of

transforming

all

things," the statement added.

(Commenting

on

the

Pope's

momentous

ecumenical

move,

Terian

recalls

that

"while

Armenians

were

about

to

canonize

their

martyred

saints

of

a

hundred

years

ago,

the

Papal

declaration

reminded

them

of

one

of

their

saints

who

died

a

thousand

years

ago.This

should

imply

that

identity

and

perpetuity

for

Armenians

lies

not

only

in

the

collective

remembrance

of their recent past, however tragic, but also in their centuries-old Christian heritage.")

The

significance

of

Terian's

latest

oeuvre,

a

timely

token

of

that

heritage,

cannot

be

understated.

Were

it

not

for

his

polished

and

inspired

translation,

the

anthology

of

Naregatsi's unparalleled liturgical masterpieces would have otherwise been lost to us.

As

UCLA

professor

of

Armenian

studies

S.

Peter

Cowe

notes,

Dr

Terian

"has

placed

us

in

his

debt

again

by

transmitting

these

pearls

of

mediaeval

Armenian

poetry

from

the

preserve

of

a

small

group

of

experts

into

the

public

domain

through

his

accurate

idiomatic

translation

and

helpful notes."

Theo

Maarten

van

Lint,

Calouste

Gulbenkian

professor

of

Armenian

studies

at

Oxford

University,

for

whom

Terian's

book

is

"magnificent,

groundbreaking"

goes

so

far

as

to

describe

Naregatsi's work as "an act of Divine grace."

"I go up to Jerusalem

"To that city built by God

"To

that

beautifully

built

temple

.

.

."

cries

out

Naregatsi

in

one

of

the

odes

translated

by

Terian, giving tongue to a universal yearning for the ethereal.

More

than

any

other

geographical

or

metaphorical

entity,

Jerusalem

remains

forever

the

symbol of that longing.

For

Terian,

and

all

the

Armenians

who

grew

up

in

the

Old

City,

trod

its

cobblestoned

alleys

and drank its waters, Jerusalem is more than a place in the heart.

It

is

where

life

begins,

where

humanity

is

born

and

rejuvenated,

physically

and

spiritually.

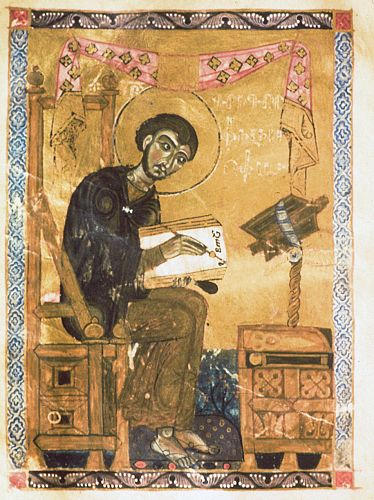

A thousand years ago, a monk in a distant monastery in the western

Armenian province of Reshdunik, picked up a reed pen and began etching

out what would later become known as the first great Armenian mystic and

liturgical poetry.