Armenian Jerusalem

The checkered history of the Armenians in Jerusalem, with their

remarkable achievements [among them the setting up of the

city's first photographic studio and printing press] have been

relatively well documented over the years by Western scholars

fascinated by this remote remnant of an exotic race.

Although diaspora Armenians themselves have been demonstrably lax in chronicling the endeavors of their compatriots in Jerusalem the gap left by such illustrious historians as Hovhanissian, Ormanian, Savalanyantz and Sanjian has been admirably filled by objective observers, particularly from Europe. A definitive account (if there ever can be one) by a native Armenian Jerusalemite is long overdue, the lapse difficult to explain. Hopefully, it is perhaps not necessarily a reflection of a lack of interest, since there have been a few laudable efforts by Armenians in Jerusalem, among them Kevork Hintlian and the late Assadour Antreassian, to tell their tale. At the same time, with the advent of Patriarch Torkom Manoogian and the refreshing new breezes he brought with him, the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem has in recent years regularly kept the world informed of goings on among the Armenians in the Holy Land through its Press Office. Armenophiles need not despair therefore, since if we can't do it ourselves, we can always count on the next best thing, have our story told by 'odar's. The latest such endeavor is by three 'odar's who have lived and taught among the Armenians in Jerusalem and have gained a firsthand sampling of their way of life. "The Armenians in Jerusalem and the Holy Land," put out by Belgium's Peeters publishing firm under the auspices of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem's Armenian studies department, provides thoughtful reading for everyone interested in this tiny enclave of unforgettable people. The book has been edited by a trio of leading armenologists, Michael Stone and his wife Nira, native Israelis, and Roberta Ervine, who hails from the US. The 300-page tome comprises a formidably impressive volume of papers delivered at scholarly gatherings held to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Armenian studies at the Hebrew University, in what the editors hope will "form a contribution to the investigation of the Armenian presence in the Holy Land." Despite the relentless attrition among the city's Armenians that has decimated the once 25,000 strong community as whole families have packed up and left, the editors strike an upbeat note encouraged by recent archaeological finds, certain that the future "doubtless holds more exciting discoveries." Serious scholars can also look for assistance in their research to the Patriarchate's manuscript library, the world's second largest such collection, although a study of these MSS is still in its infancy. The book covers a wide range of topics, including the arrival of the first Armenian pilgrims, a reassessment of two incomparable Armenian mosaics dating back to the 5th century, the contribution of Armenian Jerusalem to Armenians in America, and a delightful piece on the lilting dialect of the city's 'kaghakatsi.” This paper, by Bert Vaux, is bound to elicit wide grins, and perhaps feelings of nostalgia among elderly 'kaghakatsi' Armenian readers. The current crop of these natives has mostly weaned itself from the quaint twang of its Arabic augmented dialect, this "unique mélange of distinctive elements," but the scattered old matriarchs and patriarchs [of whom there were at least three in Jerusalem, and another two in Sydney, when the paper was written, contrary to Vaux's assertion that only one completely fluent speaker remains, in New York], are still going strong at it. Unfortunately, we may have to agree with Vaux's assumption that the dialect will not be passed on to future generations. Certainly, with the proliferation of Hebrew speakers among the Armenians of Jerusalem, the monopolistic Arabic language influence, has begun to wane. And the rising generation of 'kaghakatsi's, admittedly few in number, have few or no role models left to inherit their distinctive linguistic tradition. The future may hold only a queasy promise for the Armenians of Jerusalem, caught as they are in the vice of regional political uncertainty and unnatural attrition, but the story of Jerusalem, whenever and wherever it is told, will always be spiced with the unique flavor of the Armenian cauldron. We can always count on Michael and Nina Stone, and Roberta Ervine, and a gallery of distinguished armenologists and armenophiles, to keep rekindling the flame under it. "The Armenians in Jerusalem and the Holy Land" offers erudite reading for us while at the same time giving us ample food for thought. The book could have done with more illustrations, with perhaps one or two color reproductions, of a Toros Roslin painting or the haunting Eustacius mosaic, discovered ten years ago. What reader would balk at the extra cost when such treasure is on offer?

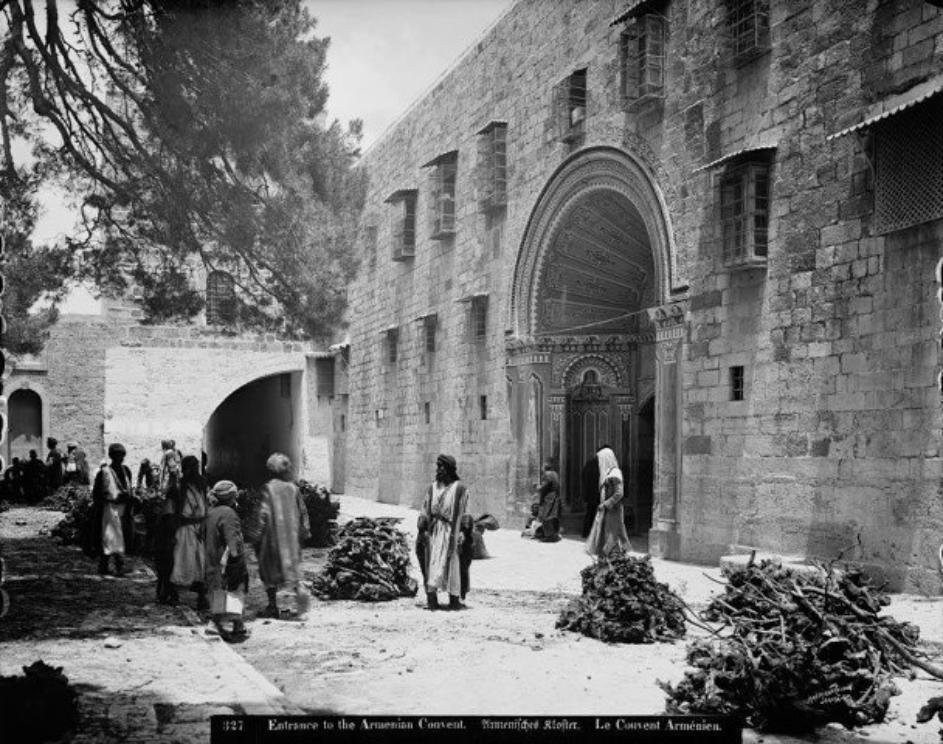

Pilgrims and merchants at St James