Armenian Jerusalem

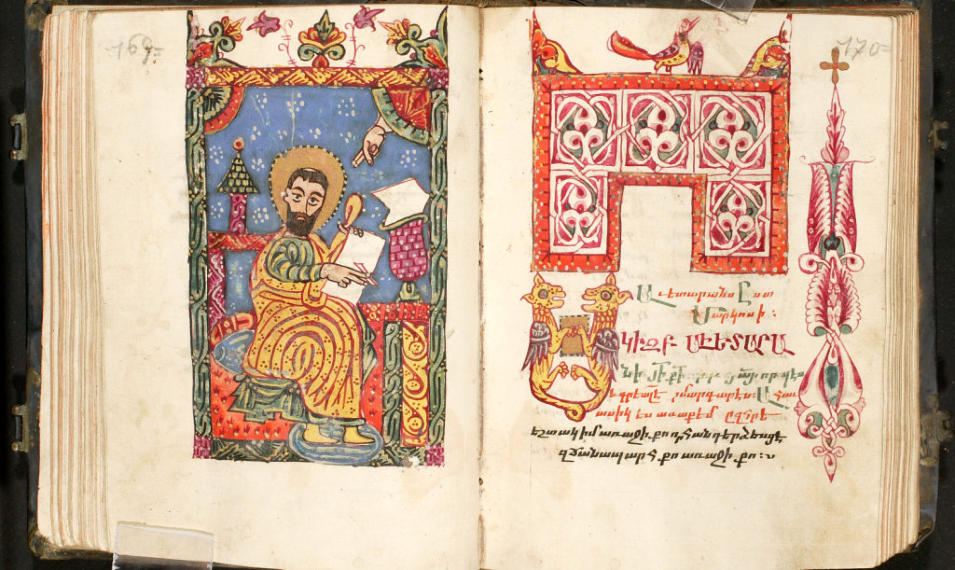

illustrated gospel manuscript

For years beyond count they have been languishing undisturbed,

save for an occasional peek, in the cavernous archives of the

Armenian Patriarchate of St James, in the Old City of Jerusalem.

For years beyond count they have been languishing undisturbed, save for an occasional peek, in the cavernous archives of the Armenian Patriarchate of St James, in the Old City of Jerusalem. Three fat tomes of painstakingly meticulous script, with frequent lapses into flowery forays, the official registers recording the births, baptisms, marriages and deaths of the denizens of the city's Armenian Quarter, the kaghakatsis. The passage of time has taken its usual toll of the 150 pages, but the onslaught has been mercifully mild. Except for places where the faded writing makes for difficult reading, the entries penned by the ancient clerks have retained most of their pristine clarity. Locked away within the hallowed confines of the Convent of St James, the pages rarely again saw the light of day after being bound into books. They would only be brought out when some one needed to consult them and verify a date or name. Only to be re-consigned later to relative oblivion. Until now. In keeping with his wish to exude a measure of "glasnost" into the moribund life of the Armenians of Jerusalem, and to promote efforts by the kaghakatsi Armenian Family Tree Project to preserve the history and culture of his Old City community, the Patriarch, Archbishop Torkom Manoogian, has agreed to have the contents of the registers made available for study and research by the Project organizers. The Patriarchate also gave the organizers permission to copy the information in the books, under proper security and privacy safeguards. To facilitate this arduous task, the Patriarchate even offered to house and feed the researcher for the few weeks needed for the job. With the support and blessing of the Patriarchate in hand, the Project organizers then faced the problem of deciding on the safest and easiest way to undertake the copying of the registers. One option would have been to use a hand-held scanner. Another, a photocopier. But the delicate and brittle texture of the paper has precluded these and it has finally been decided to use a camera and photograph the pages instead. This would have to be done by a professional, not just anyone with a camera. The cost would be considerable for the Project which has no budget of its own, and is run entirely on a voluntary basis. It was at this point that the cavalry arrived, in the form of Garo Nalbandian, one of Jerusalem's foremost photographers whose work appears regularly in leading local and international publications and venues. Once Garo knew of the nature of the project, he promptly offered his services to the organizers. He would waive his fee. "If you are doing a 'labor of love', my dad is willing to help too," his son and assistant, Hovsep, told the organizers. "So he will do it for free." The organizers were ecstatic at this new and "welcome" development. "The man is so busy he can scarcely scratch his head, yet here he is donating his time and services to a project for nothing, when he could have made a package for himself," a kaghakatsi Armenian commented. The fact that his wife is a kaghakatsi herself, a member of the Toumayan clan, would have also influenced his decision. Besides, he is no stranger to the Patriarchate and has been involved in some of its preservation projects, among them the Edward and Helen Mardigian Museum, for which he helped create the graphic display of old Armenian coins. The registers are a rare and delightful treasure trove. They speak volumes. A quick look reveals their quaint twist: apparently, in the old days, clerks had developed only a pedestrian attitude towards the art and science of archiving, as evidenced by the fact that they were not particular about recording or tracing accurate patronymics: often, people are referred to by a sobriquet instead of a surname. Thus it is not surprising to find "tertzag (tailor) Garabed" rubbing shoulders with "sabounji (soap maker/seller?) Tavit," "badgerahan (photographer) Hagop," "sevaji (shoemaker) Sahag", "Krikor vosgerich (goldsmith)" . . . Now that access to these registers has been secured, the Project enters a challenging and definitive phase. The Family Tree online database already houses over 2,300 names belonging to some 50 clans: the genealogical information there has to be validated by the contents of the kaghakatsi registers. Apparently these documents are not the only legacy of the ancestors of the kaghakatsis living in the Armenian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem. Patriarchate sources believe there is a mountain of data about this community being retained in various forms at the Patriarchate. "There must be enough material there to keep a researcher happily busy for a lifetime," one source said. Like the registers, these unknown archives also face the threat of degradation unless urgent measures are taken to preserve them. Manoogian would like nothing more than to computerize all Patriarchate archives, but such a daunting undertaking would tax the meager resources of St James. Nevertheless, he continues to pursue his dream of propelling this august establishment into the technological age, a move that has seen the Patriarchate go online and its offices linked by a web network. Gone are the stolid, lumbering Remington typewriters and messy ribbons, making way for sleek PC's running the latest operating systems. And accountability and openness have become the order of the day. Armenian Jerusalem has come a long way. It would not have been possible without sabounji Tavit, sevaji Sahag, tertzag Garabed or badgerahan Hagog. "Their legacy lives on in us, and will continue down the line, as long as there is one single kaghakatsi still breathing on this planet," as one community leader puts it.